#Content Moderators

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

#Social Media Content Moderation#United States#social networking sites#objectionable content#Content moderation services#content moderators#social media platforms#Pre-moderation#post-moderation#reactive moderation#spam contents#Unwanted Contents#facebook#linkdin#twiitter#Instagram#YouTube#Tumblr#TikTok

1 note

·

View note

Text

today in "content moderation is thankless work done by underpaid, overworked contractors, largely in the global south":

Carolina, a former TikTok moderator who worked remotely for Teleperformance, a Paris-based company offering moderation services and earned $10 a day, said she had to keep her camera continuously on during her night shift, TBIJ reported. The company also told her that no one should be in view of the camera and was only allowed a drink in a transparent cup on her desk.

[...]

Luis, 28, worked night shifts moderating videos for TikTok. He listed to the outlet the kind of content he sees regularly: "Murder, suicide, pedophilia, pornographic content, accidents, cannibalism."

(and before anyone gets needlessly smug and tries to spin this as a problem unique to tiktok: it's not. not by a long shot. content moderation across the board is a thorny issue that requires huge amounts of real human oversight, which is made worse by the fact that so much of it is low-paying, soul-crushing work (or, in some cases like reddit, completely unpaid work done by volunteers). facebook in particular has been mistreating its content moderators for years now.)

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

#memes#fresh memes#dankest memes#funny content#funny tumblr#best memes#new memes#relatable memes#lol memes#life#tumblr memes#memes image#meme#animal memes#animals#Bee#moderation

3K notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Content moderators? Ecco cosa si nasconde dietro il loro lavoro☝🏻

Pensate di conoscere tutte le persone che lavorano dietro ai social? Ma soprattutto, pensate che quello dei content moderators sia un lavoro come un altro? Vi possiamo assicurare che non è così. Adesso vi sveleremo il lato nascosto delle vostre piattaforme preferite, con effetti che mai avreste immaginato.

Buona visione!

Non dimenticatevi di farci sapere cosa ne pensate nei commenti!

#digitalcafe#content moderators#social media#violenza#google#facebook#effetti psicologici#sfruttamento#thecleaners#video#contenuti#delete#ignore

1 note

·

View note

Text

Better failure for social media

Content moderation is fundamentally about making social media work better, but there are two other considerations that determine how social media fails: end-to-end (E2E), and freedom of exit. These are much neglected, and that’s a pity, because how a system fails is every bit as important as how it works.

Of course, commercial social media sites don’t want to be good, they want to be profitable. The unique dynamics of social media allow the companies to uncouple quality from profit, and more’s the pity.

Social media grows thanks to network effects — you join Twitter to hang out with the people who are there, and then other people join to hang out with you. The more users Twitter accumulates, the more users it can accumulate. But social media sites stay big thanks to high switching costs: the more you have to give up to leave a social media site, the harder it is to go:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

Nature bequeaths some in-built switching costs on social media, primarily the coordination problem of reaching consensus on where you and the people in your community should go next. The more friends you share a social media platform with, the higher these costs are. If you’ve ever tried to get ten friends to agree on where to go for dinner, you know how this works. Now imagine trying to get all your friends to agree on where to go for dinner, for the rest of their lives!

But these costs aren’t insurmountable. Network effects, after all, are a double-edged sword. Some users are above-average draws for others, and if a critical mass of these important nodes in the network map depart for a new service — like, say, Mastodon — that service becomes the presumptive successor to the existing giants.

When that happens — when Mastodon becomes “the place we’ll all go when Twitter finally becomes unbearable” — the downsides of network effects kick in and the double-edged sword begins to carve away at a service’s user-base. It’s one thing to argue about which restaurant we should go to tonight, it’s another to ask whether we should join our friends at the new restaurant where they’re already eating.

Social media sites who want to keep their users’ business walk a fine line: they can simply treat those users well, showing them the things they ask to see, not spying on them, paying to police their service to reduce harassment, etc. But these are costly choices: if you show users the things they ask to see, you can’t charge businesses to show them things they don’t want to see. If you don’t spy on users, you can’t sell targeting services to people who want to force them to look at things they’re uninterested in. Every moderator you pay to reduce harassment draws a salary at the expense of your shareholders, and every catastrophe that moderator prevents is a catastrophe you can’t turn into monetizable attention as gawking users flock to it.

So social media sites are always trying to optimize their mistreatment of users, mistreating them (and thus profiting from them) right up to the point where they are ready to switch, but without actually pushing them over the edge.

One way to keep dissatisfied users from leaving is by extracting a penalty from them for their disloyalty. You can lock in their data, their social relationships, or, if they’re “creators” (and disproportionately likely to be key network nodes whose defection to a rival triggers mass departures from their fans), you can take their audiences hostage.

The dominant social media firms all practice a low-grade, tacit form of hostage-taking. Facebook downranks content that links to other sites on the internet. Instagram prohibits links in posts, limiting creators to “Links in bio.” Tiktok doesn’t even allow links. All of this serves as a brake on high-follower users who seek to migrate their audiences to better platforms.

But these strategies are unstable. When a platform becomes worse for users (say, because it mandates nonconsensual surveillance and ramps up advertising), they may actively seek out other places on which to follow each other, and the creators they enjoy. When a rival platform emerges as the presumptive successor to an incumbent, users no longer face the friction of knowing which rival they should resettle to.

When platforms’ enshittification strategies overshoot this way, users flee in droves, and then it’s time for the desperate platform managers to abandon the pretense of providing a public square. Yesterday, Elon Musk’s Twitter rolled out a policy prohibiting users from posting links to rival platforms:

https://web.archive.org/web/20221218173806/https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/social-platforms-policy

This policy was explicitly aimed at preventing users from telling each other where they could be found after they leave Twitter:

https://web.archive.org/web/20221219015355/https://twitter.com/TwitterSupport/status/1604531261791522817

This, in turn, was a response to many users posting regular messages explaining why they were leaving Twitter and how they could be found on other platforms. In particular, Twitter management was concerned with departures by high-follower users like Taylor Lorenz, who was retroactively punished for violating the policy, though it didn’t exist when she violated it:

https://deadline.com/2022/12/washington-post-journalist-taylor-lorenz-suspended-twitter-1235202034/

As Elon Musk wrote last spring: “The acid test for two competing socioeconomic systems is which side needs to build a wall to keep people from escaping? That’s the bad one!”

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1533616384747442176

This isn’t particularly insightful. It’s obvious that any system that requires high walls and punishments to stay in business isn’t serving its users, whose presence is attributable to coercion, not fulfillment. Of course, the people who operate these systems have all manner of rationalizations for them.

The Berlin Wall, we were told, wasn’t there to keep East Germans in — rather, it was there to keep the teeming hordes clamoring to live in the workers’ paradise out. In the same way, platforms will claim that they’re not blocking outlinks or sideloading because they want to prevent users from defecting to a competitor, but rather, to protect those users from external threats.

This rationalization quickly wears thin, and then new ones step in. For example, you might claim that telling your friends that you’re leaving and asking them to meet you elsewhere is like “giv[ing] a talk for a corporation [and] promot[ing] other corporations”:

https://mobile.twitter.com/mayemusk/status/1604550452447690752

Or you might claim that it’s like “running Wendy’s ads [on] McDonalds property,” rather than turning to your friends and saying, “The food at McDonalds sucks, let’s go eat at Wendy’s instead”:

https://twitter.com/doctorow/status/1604559316237037568

The truth is that any service that won’t let you leave isn’t in the business of serving you, it’s in the business of harming you. The only reason to build a wall around your service — to impose any switching costs on users- is so that you can fuck them over without risking their departure.

The platforms want to be Anatevka, and we the villagers of Fiddler On the Roof, stuck plodding the muddy, Cossack-haunted roads by the threat of losing all our friends if we try to leave:

https://doctorow.medium.com/how-to-leave-dying-social-media-platforms-9fc550fe5abf

That’s where freedom of exit comes in. The public should have the right to leave, and companies should not be permitted to make that departure burdensome. Any burdens we permit companies to impose is an invitation to abuse of their users.

This is why governments are handing down new interoperability mandates: the EU’s Digital Markets Act forces the largest companies to offer APIs so that smaller rivals can plug into them and let users walkaway from Big Tech into new kinds of platforms — small businesses, co-ops, nonprofits, hobby sites — that treat them better. These small players are overwhelmingly part of the fediverse: the federated social media sites that allow users to connect to one another irrespective of which server or service they use.

The creators of these platforms have pledged themselves to freedom of exit. Mastodon ships with a “Move Followers” and “Move Following” feature that lets you quit one server and set up shop on another, without losing any of the accounts you follow or the accounts that follow you:

https://codingitwrong.com/2022/10/10/migrating-a-mastodon-account.html

This feature is as yet obscure, because the exodus to Mastodon is still young. Users who flocked to servers without knowing much about their managers have, by and large, not yet run into problems with the site operators. The early trickle of horror stories about petty authoritarianism from Mastodon sysops conspicuously fail to mention that if the management of a particular instance turns tyrant, you can click two links, export your whole social graph, sign up for a rival, click two more links and be back at it.

This feature will become more prominent, because there is nothing about running a Mastodon server that means that you are good at running a Mastodon server. Elon Musk isn’t an evil genius — he’s an ordinary mediocrity who lucked into a lot of power and very little accountability. Some Mastodon operators will have Musk-like tendencies that they will unleash on their users, and the difference will be that those users can click two links and move elsewhere. Bye-eee!

Freedom of exit isn’t just a matter of the human right of movement, it’s also a labor issue. Online creators constitute a serious draw for social media services. All things being equal, these services would rather coerce creators’ participation — by holding their audiences hostage — than persuade creators to remain by offering them an honest chance to ply their trade.

Platforms have a variety of strategies for chaining creators to their services: in addition to making it harder for creators to coordinate with their audiences in a mass departure, platforms can use DRM, as Audible does, to prevent creators’ customers from moving the media they purchase to a rival’s app or player.

Then there’s “freedom of reach”: platforms routinely and deceptively conflate recommending a creator’s work with showing that creator’s work to the people who explicitly asked to see it.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/10/e2e/#the-censors-pen

When you follow or subscribe to a feed, that is not a “signal” to be mixed into the recommendation system. It’s an order: “Show me this.” Not “Show me things like this.”

Show.

Me.

This.

But there’s no money in showing people the things they tell you they want to see. If Amazon showed shoppers the products they searched for, they couldn’t earn $31b/year on an “ad business” that fills the first six screens of results with rival products who’ve paid to be displayed over the product you’re seeking:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/28/enshittification/#relentless-payola

If Spotify played you the albums you searched for, it couldn’t redirect you to playlists artists have to shell out payola to be included on:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

And if you only see what you ask for, then product managers whose KPI is whether they entice you to “discover” something else won’t get a bonus every time you fatfinger a part of your screen that navigates you away from the thing you specifically requested:

https://doctorow.medium.com/the-fatfinger-economy-7c7b3b54925c

Musk, meanwhile, has announced that you won’t see messages from the people you follow unless they pay for Twitter Blue:

https://www.wired.com/story/what-is-twitter-blue/

And also that you will be nonconsensually opted into seeing more “recommended” content from people you don’t follow (but who can be extorted out of payola for the privilege):

https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/Twitter-Expands-Content-Recommendations/637697/

Musk sees Twitter as a publisher, not a social media site:

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1604588904828600320

Which is why he’s so indifferent to the collateral damage from this payola/hostage scam. Yes, Twitter is a place where famous and semi-famous people talk to their audiences, but it is primarily a place where those audiences talk to each other — that is, a public square.

This is the Facebook death-spiral: charging to people to follow to reach you, and burying the things they say in a torrent of payola-funded spam. It’s the vision of someone who thinks of other people as things to use — to pump up your share price or market your goods to — not worthy of consideration.

As Terry Pratchett’s Granny Weatherwax put it: “Sin is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That’s what sin is.”

Mastodon isn’t perfect, but its flaws are neither fatal nor permanent. The idea that centralized media is “easier” surely reflects the hundreds of billions of dollars that have been pumped into refining social media Roach Motels (“users check in, but they don’t check out”).

Until a comparable sum has been spent refining decentralized, federated services, any claims about the impossibility of making the fediverse work for mass audiences should be treated as unfalsifiable, motivated reasoning.

Meanwhile, Mastodon has gotten two things right that no other social media giant has even seriously attempted:

I. If you follow someone on Mastodon, you’ll see everything they post; and

II. If you leave a Mastodon server, you can take both your followers and the people you follow with you.

The most common criticism of Mastodon is that you must rely on individual moderators who may be underresourced, incompetent on malicious. This is indeed a serious problem, but it isn’t the same serious problem that Twitter has. When Twitter is incompetent, malicious, or underresourced, your departure comes at a dear price.

On Mastodon, your choice is: tolerate bad moderation, or click two links and move somewhere else.

On Twitter, your choice is: tolerate moderation, or lose contact with all the people you care about and all the people who care about you.

The interoperability mandates in the Digital Markets Act (and in the US ACCESS Act, which seems unlikely to get a vote in this session of Congress) only force the largest platforms to open up, but Mastodon shows us the utility of interop for smaller services, too.

There are lots of domains in which “dominance” shouldn’t be the sole criteria for whether you are expected to treat your customers fairly.

A doctor with a small practice who leaks all ten patients’ data harms those patients as surely as a hospital system with a million patients would have. A small-time wedding photographer who refuses to turn over your pictures unless you pay a surprise bill is every bit as harmful to you as a giant chain that has the same practice.

As we move into the realm of smalltime, community-oriented social media servers, we should be looking to avoid the pitfalls of the social media bubble that’s bursting around us. No matter what the size of the service, let’s ensure that it lets us leave, and respects the end-to-end principle, that any two people who want to talk to each other should be allowed to do so, without interference from the people who operate their communications infrastructure.

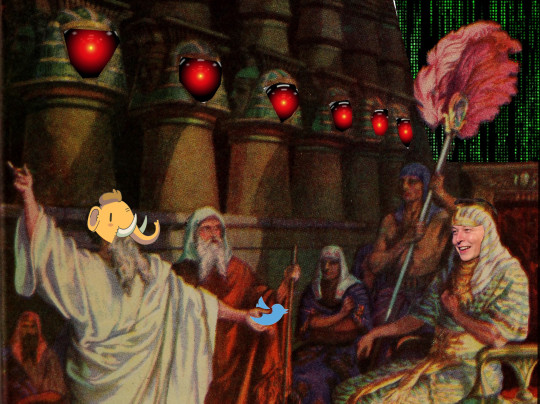

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

Heisenberg Media (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elon_Musk_-_The_Summit_2013.jpg

CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

[Image ID: Moses confronting the Pharaoh, demanding that he release the Hebrews. Pharaoh’s face has been replaced with Elon Musk’s. Moses holds a Twitter logo in his outstretched hand. The faces embossed in the columns of Pharaoh’s audience hall have been replaced with the menacing red eye of HAL9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey. The wall over Pharaoh’s head has been replaced with a Matrix ‘code waterfall’ effect. Moses’s head has been replaced with that of the Mastodon mascot.]

#pluralistic#e2e#end-to-end#freedom of reach#mastodon#interoperability#social media#twitter#economy#creator economy#artists rights#content moderation#como#right of exodus#let my tweeters go#exodus#right of exit#technological self-determination

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

6 TYPES OF CONTENT MODERATION SERVICES OFFERED BY TASKMO!

Everyday several individuals across the globe are creating massive amounts of content everyday and they are being distributed everywhere, all across the web. Several amounts of content in the form of text, pictures, recordings, blogs, podcasts, surveys, inputs and so much more are being put up on the internet everyday.

Today with the increase in global presence and the number of brands operating online, it is important for brands and large corporations to monitor this large amount of content generated by users. An indispensable amount of content is put out on websites, discussion forums, journals and so much more. At this point, when third party content is put out on the internet it’s important for brands to proficiently control their brand presence online and show a positive image amongst their clients. If you are looking for content moderation services, or if you want your brand content to be monitored, visit Taskmo. At Taskmo, we offer highly specialised and experienced content moderation specialists and our content moderation services are unmatched. Our content moderation services are as follows;

Picture Moderation

The first thing for a brand to monitor is the photographs, pictures and any images that are associated with the brand. Our team of skilled content moderators and content specialists work in groups in and out and monitor each and every picture that your brand or any third-party puts out on the web. In most cases, since pictures affect clients in an indirect manner and it is important to keep all our eyes on the same. At Taskmo, we ensure that our content moderators and content specialists keep up with the latest updates of your brand and ensure that 100% precision is kept within a quick turnaround time. Our talented content moderators ensure that with minimal tweaks and changes we administer the brand in an incredibly efficient manner. Regardless of whether the pictures are profile pictures from public or private or some other collections our content moderators at Taskmo, will ensure that we provide you customised picture moderations services in accordance to the needs of your brands.

Video Moderation

Video moderation is highly essential for your brand to ensure that there exists no flaws in your brand image. Regardless of whether you need a general video balance arrangement or a redid arrangement, we do everything for you. Our content moderators at Taskmo, will ensure that we add an extra layer of value control that guarantees every one of the videos or recordings are according to customer's strategies and rules. Our talented content specialists will scan the all web-based media channels or some other client produced recordings and guarantee that the recordings follow severe rules and banner unseemly recordings. Likewise, we also follow video control strategies, for example, start to finish video balance, actually picture and progress balance. At Taskmo, we also give month to month reports laying out the amount of recordings directed and the activity taken on every one of the recordings.

Text Moderation

If there should be an occurrence of an online intelligent local area, it turns out to be exceptionally basic to oversee client created content (UGC) as the brand notoriety depends on it. It is essential to guarantee that solitary proper client produced content is posted on the site by screening and sifting (for example remark balance) for mal-content. Neglecting to do as such could seriously affect client traffic, organization brand and online client experience.Under text moderation we include remarks, tweets, posts, surveys and so on. Our group content moderators continuously manage a wide range of client produced content to guard online local areas and is easy to understand.

Instagram Moderation

Instagram has turned out to be an important social media channel and over 7.77 million users spend over two to three hours on the platform daily. With the large amount of viewership that exists on the platform daily, it is a space for every brand to watch out. Everyday there people feed a large number of videos, photographs, reels and so much more. At Taskmo, we ensure that we scan every content that is put out by your brand and other user generated content and ensure that they are accurate and there is no mal-content.

Tweet Moderation

Recently, Twitter has taken the middle stage in friendly marketing, it is significant that every single tweet about the brand is overseen on schedule. At Taskmo, we have the capability to oversee content on Twitter and ensure that they are incredible.

LinkedIn Moderation

For most businesses and brands today LinkedIn is a platform to showcase their company, their work culture, their employees, their products and services and so much more. Out of all the social media channels, LinkedIn is a space for businesses to make their impressions on potential businessmen,partners and customers.

At Taskmo, our content moderation services are offered under three unique and distinct categories, they include;

Pre Distribution - Under this category, we ensure that our content moderators and content specialists moderate the content before they are distributed to the world wide web.

Post Distribution - In this category, our content specialists and content moderators look into all forms of user generated content after it is distributed into the particular social media channels or other distribution platforms.

Custom Moderation - The custom moderation is a custom category/custom service, where our content moderators and specialists watch over distributed content, in case they seem unseemly.

If you want your brand’s content to be monitored, why wait? Visit Taskmo and avail our content moderation services and we’ll ensure that your brand image is positive and it portrays a well respected image in front of your clients.

0 notes

Link

This is depressing and true, but it did give me a good chuckle.

649 notes

·

View notes

Text

US court dismisses case against Cognizant, Facebook - Times of India

US court dismisses case against Cognizant, Facebook – Times of India

BENGALURU: A US court dismissed a petition by content moderators at Cognizant that charged the company and Facebook of failing to protect them against the psychological dangers posed by exposure to graphic images. The court said the plaintiffs had failed to establish their case. It dismissed the plaintiffs’ charges of fraudulent misrepresentation or concealment against Cognizant, and denied their…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

281 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

substack CEO

https://www.theverge.com/23681875/substack-notes-twitter-elon-musk-content-moderation-free-speech

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freedom of reach IS freedom of speech

The online debate over free speech suuuuucks, and, amazingly, it’s getting worse. This week, it’s the false dichotomy between “freedom of speech” and “freedom of reach,” that is, the debate over whether a platform should override your explicit choices about what you want to see:

https://seekingalpha.com/news/3849331-musk-meets-twitter-staff-freedom-of-reach-new-ideas-on-human-verification

It’s wild that we’re still having this fight. It is literally the first internet fight! The modern internet was born out of an epic struggled between “Bellheads” (who believed centralized powers should decide how you used networks) and “Netheads” (who believed that services should be provided and consumed “at the edge”):

https://www.wired.com/1996/10/atm-3/

The Bellheads grew out of the legacy telco system, which was committed to two principles: universal service and monetization. The large telcos were obliged to provide service to everyone (for some value of “everyone”), and in exchange, they enjoyed a monopoly over the people they connected to the phone system.

That meant that they could decide which services and features you had, and could ask the government to intervene to block competitors who added services and features they didn’t like. They wielded this power without restraint or mercy, targeting, for example, the Hush-A-Phone, a cup you stuck to your phone receiver to muffle your speech and prevent eavesdropping:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hush-A-Phone

They didn’t block new features for shits and giggles, though — the method to this madness was rent-extraction. The iron-clad rule of the Bell System was that anything that improved on the basic service had to have a price-tag attached. Every phone “feature” was a recurring source of monthly revenue for the phone company — even the phone itself, which you couldn’t buy, and had to rent, month after month, year after year, until you’d paid for it hundreds of times over.

This is an early and important example of “predatory inclusion”: the monopoly carriers delivered universal service to all of us, but that was a prelude to an ugly, parasitic, rent-seeking way of doing business:

https://lpeproject.org/blog/predatory-inclusion-a-long-view-of-the-race-for-profit/

It wasn’t just the phone that came with an unlimited price-tag: everything you did with the phone was also a la carte, like the bananas-high long-distance charges, or even per-minute charges for local calls. Features like call waiting were monetized through recurring monthly charges, too.

Remember when Caller ID came in and you had to pay $2.50/month to find out who was calling you before you answered the phone? That’s a pure Bellhead play. If we applied this principle to the internet, then you’d have to pay $2.50/month to see the “from” line on an email before you opened it.

Bellheads believed in “smart” networks. Netheads believed in what David Isenberg called “The Stupid Network,” a “dumb pipe” whose only job was to let some people send signals to other people, who asked to get them:

https://www.isen.com/papers/Dawnstupid.html

This is called the End-to-End (E2E) principle: a network is E2E if it lets anyone receive any message from anyone else, without a third party intervening. It’s a straightforward idea, though the spam wars brought in an important modification: the message should be consensual (DoS attacks, spam, etc don’t count).

The degradation of the internet into “five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of text from the other four” (h/t Tom Eastman) meant the end of end-to-end. If you’re a Youtuber, Tiktoker, tweeter, or Facebooker, the fact that someone explicitly subscribed to your feed does not mean that they will, in fact, see your feed.

The platforms treat your unambiguous request to receive messages from others as mere suggestions, a “signal” to be mixed into other signals in the content moderation algorithm that orders your feed, mixing in items from strangers whose material you never asked to see.

There’s nothing wrong in principal with the idea of a system that recommends items from strangers. Indeed, that’s a great way to find people to follow! But “stuff we think you’ll like” is not the same category as “stuff you’ve asked to see.”

Why do companies balk at showing you what you’ve asked to be shown? Sometimes it’s because they’re trying to be helpful. Maybe their research, or the inferences from their user surveillance, suggests that you actually prefer it that way.

But there’s another side to this: a feed composed of things from people is fungible. Theoretically, you could uproot that feed from one platform and settle it in another one — if everyone you follow on Twitter set up an account on Mastodon, you could use a tool like Movetodon to refollow them there and get the same feed:

https://www.movetodon.org/

A feed that is controlled by a company using secret algorithms is much harder for a rival to replicate. That’s why Spotify is so hellbent on getting you to listen to playlists, rather than albums. Your favorite albums are the same no matter where you are, but playlists are integrated into services.

But there’s another side to this playlistification of feeds: playlists and other recommendation algorithms are chokepoints: they are a way to durably interpose a company between a creator and their audience. Where you have chokepoints, you get chokepoint capitalism:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

That’s when a company captures an audience inside a walled garden and then extracts value from creators as a condition of reaching them, even when the audience requests the creator’s work. With Spotify, that manifests as payola, where creators have to pay for inclusion on playlists. Spotify uses playlists to manipulate audiences into listening to sound-alikes, silently replacing the ambient artists that listeners tune in to hear with work-for-hire musicians who aren’t entitled to royalties.

Facebook’s payola works much the same: when you publish a post on Facebook, you have to pay to boost it if you want it to reach the people who follow you — that is, the people who signed up to see what you post. Facebook may claim that it does this to keep its users’ feeds “uncluttered” but that’s a very thin pretense. Though you follow friends and family on Facebook, your feed is weighted to accounts willing to cough up the payola to reach you.

The “uncluttering” excuse wears even thinner when you realize that there’s no way to tell a platform: “This isn’t clutter, show it to me every time.” Think of how the cartel of giant email providers uses the excuse of spam to block mailing lists and newsletters that their users have explicitly signed up for. Those users can fish those messages out of their spam folders, they can add the senders to their address books, they can write an email rule that says, “If sender is X, then mark message as ‘not spam’” and the messages still go to spam:

https://doctorow.medium.com/dead-letters-73924aa19f9d

One sign of just how irredeemably stupid the online free expression debate is that we’re arguing over stupid shit like whether unsolicited fundraising emails from politicians should be marked as spam, rather than whether solicited, double-opt-in newsletters and mailing lists should be:

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/republican-committee-sues-google-over-email-spam-filters/

When it comes to email, the stuff we don’t argue about is so much more important than the stuff we do. Think of how email list providers blithely advertise that they can tell you the “open rate” of the messages that you send — which means that they embed surveillance beacons (tracking pixels) in every message they send:

https://www.wired.com/story/how-email-open-tracking-quietly-took-over-the-web/

Sending emails that spy on users is gross, but the fucking disgusting part is that our email clients don’t block spying by default. Blocking tracking pixels is easy as hell, and almost no one wants to be spied on when they read their email! The onboarding process for webmail accounts should have a dialog box that reads, “Would you like me to tell creepy randos which emails you read?” with the default being “Fuck no!” and the alternative being “Hurt me, Daddy!”

If email providers wanted to “declutter” your inbox, they could offer you a dashboard of senders whose messsages you delete unread most of the time and offer to send those messages straight to spam in future. Instead they nonconsensually intervene to block messages and offer no way to override those blocks.

When it comes to recommendations, companies have an unresolvable conflict of interest: maybe they’re interfering with your communications to make your life better, or maybe they’re doing it to make money for their shareholders. Sorting one from the other is nigh impossible, because it turns on the company’s intent, and it’s impossible to read product managers’ minds.

This is intrinsic to platform capitalism. When platforms are getting started, their imperative is to increase their user-base. To do that, they shift surpluses to their users — think of how Amazon started off by subsidizing products and deliveries.

That lured in businesses, and shifted some of that surplus to sellers — giving fat compensation to Kindle authors and incredible reach to hard goods sellers in Marketplace. More sellers brought in more customers, who brought in more sellers.

Once sellers couldn’t afford to leave Amazon because of customers, and customers couldn’t afford to leave Amazon because of sellers, the company shifted the surplus to itself. It imposed impossible fees on sellers — Amazon’s $31b/year “advertising” business is just payola — and when sellers raised prices to cover those fees, Amazon used “Most Favored Nation” contracts to force sellers to raise prices everywhere else.

The enshittification of Amazon — where you search for a specific product and get six screens of ads for different, worse ones — is the natural end-state of chokepoint capitalism:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/28/enshittification/#relentless-payola

That same enshittification is on every platform, and “freedom of speech is not freedom of reach” is just a way of saying, “Now that you’re stuck here, we’re going to enshittify your experience.”

Because while it’s hard to tell if recommendations are fair or not, it’s very easy to tell whether blocking end-to-end is unfair. When a person asks for another person to send them messages, and a third party intervenes to block those messages, that is censorship. Even if you call it “freedom of reach,” it’s still censorship.

For creators, interfering with E2E is also wage-theft. If you’re making stuff for Youtube or Tiktok or another platform and that platform’s algorithm decides you’ve broken a rule and therefore your subscribers won’t see your video, that means you don’t get paid.

It’s as if your boss handed you a paycheck with only half your pay in it, and when you asked what happened to the other half, your boss said, “You broke some rules so I docked your pay, but I won’t tell you which rules because if I did, you might figure out how to break them without my noticing.”

Content moderation is the only part of information security where security-through-obscurity is considered good practice:

https://doctorow.medium.com/como-is-infosec-307f87004563

That’s why content moderation algorithms are a labor issue, and why projects like Tracking Exposed, which reverse-engineer those algorithms to give creative workers and their audiences control over what they see, are fighting for labor rights:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/05/tracking-exposed-demanding-gods-explain-themselves

We’re at the tail end of a ghastly, 15-year experiment in neo-Bellheadism, with the big platforms treating end-to-end as a relic of a simpler time, rather than as “an elegant weapon from a more civilized age.”

The post-Twitter platforms like Mastodon and Tumblr are E2E platforms, designed around the idea that if someone asks to hear what you have to say, they should hear it. Rather than developing algorithms to override your decisions, these platforms have extensive tooling to let you fine-tune what you see.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/08/locus-of-individuation/#publish-then-filter

This tooling was once the subject of intense development and innovation, but all that research fell by the wayside with the rise of platforms, who are actively hostile to third party mods that gave users more control over their feeds:

https://techcrunch.com/2022/09/27/og-app-promises-you-an-ad-free-instagram-feed/

Alas, lawmakers are way behind the curve on this, demanding new “online safety” rules that require firms to break E2E and block third-party de-enshittification tools:

https://www.openrightsgroup.org/blog/online-safety-made-dangerous/

The online free speech debate is stupid because it has all the wrong focuses:

Focusing on improving algorithms, not whether you can even get a feed of things you asked to see;

Focusing on whether unsolicited messages are delivered, not whether solicited messages reach their readers;

Focusing on algorithmic transparency, not whether you can opt out of the behavioral tracking that produces training data for algorithms;

Focusing on whether platforms are policing their users well enough, not whether we can leave a platform without losing our important social, professional and personal ties;

Focusing on whether the limits on our speech violate the First Amendment, rather than whether they are unfair:

https://doctorow.medium.com/yes-its-censorship-2026c9edc0fd

The wholly artificial distinction between “freedom of speech” and “freedom of reach” is just more self-serving nonsense and the only reason we’re talking about it is that a billionaire dilettante would like to create chokepoints so he can extract payola from his users and meet his debt obligations to the Saudi royal family.

Billionaire dilettantes have their own stupid definitions of all kinds of important words like “freedom” and “discrimination” and “free speech.” Remember: these definitions have nothing to do with how the world’s 7,999,997,332 non-billionaires experience these concepts.

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

William Shaw Antliff (modified) https://www.macleans.ca/history/this-canadian-private-wrote-and-saved-hundreds-of-letters-during-the-first-world-war/

Public domain https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_law_of_Canada#Posthumous_works

[Image ID: A handwritten letter from a WWI soldier that has been redacted by military censors; the malevolent red eye of HAL9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey has burned through the yellowing paper.]

#pluralistic#shadowbanning#reverse chronological#spam wars#dead letters#email#read receipts#chokepoint capitalism#algorithms exposed#content moderation#como#censorship#free expression#free speech#freedom of speech#freedom of reach#e2e#end to end#tracking pixels#revealed preferences#rent seeking

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

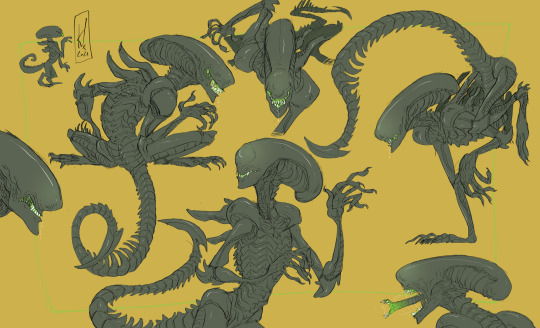

2022 Tumblr Top 10

1. 4,295 notes - Apr 26 2022

2. 753 notes - May 6 2022

3. 724 notes - Jan 16 2022

4. 662 notes - Jul 18 2022

5. 641 notes - Oct 26 2022

6. 611 notes - Oct 22 2022

7. 516 notes - Sep 28 2022

8. 495 notes - Oct 18 2022

9. 428 notes - Nov 28 2022

10. 409 notes - May 9 2022

Created by TumblrTop10

#tumblrtop10#always glad to see that my lesbian content does the best#MAY OR MAY NOT HAVE PLANS TO MAKE ZINES OF THE GALS#SAPPHOMORPHS#MY BEAUTIFUL WIFE MODER#all the xenomorphs i draw are lesbians#which is just canon obviously#but fyi if u did not know

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Section 230 (Or: How to kill the internet in one court case)

This isn't going to be quite as long as the last lengthy post, but I thought I might talk for a moment about Title 47, Section 230 in US law. Now, I myself am not an accredited lawyer nor even American, so take this with a grain of salt, but I have some experience with its implementation and how necessary it is for a site to function.

I see a number of people arguing for its removal, largely, as far as I can tell, to screw over tech companies. Now, I can certainly understand disliking Meta, Twitter, Reddit, or other such companies but I want to just explain the legal framework behind how modern social media and other content hosting sites (such as Sufficient Velocity, Archive of Our Own or tumblr itself) operate.

As a content host, you are the publisher of any content on your platform. That's why Terms of Service inevitably include language such as "you agree to grant us a non-exclusive, permanent, irrevocable, royalty-free license to Your Content as described above".

Without that license, sites simply don't have the right to publish anything you post. How does this tie into Section 230? Well, by default under US law, you are liable for anything you publish. Section 230 carves out an exception for this, as described with the following language in section(c):

"(c)Protection for “Good Samaritan” blocking and screening of offensive material

(1)Treatment of publisher or speaker: No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

(2)Civil liability: No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of—

(A) any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected; or

(B) any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in paragraph (1)." To de-legalese that, subsection(1) means that we, the content host, are not liable for user-generated content, while subsection(2) means that we are not liable for any good faith (though this is a very fuzzy term) attempt to moderate any given content. In short, subsection(1) means we don't all get arrested if someone posts CSAM, while subsection(2) means that people can't, for example, take us to court for violating their First Amendment rights for deleting a 'phobic screed or banning them as a result.

In other words, without these carve outs, we get shut down the second someone official notices illegal content on the platform — even if we ourselves are unaware.

I mention CSAM because it is by far the most common rhetorical bludgeon used to attack Section 230 — the argument is that it means content hosts are allowed to let it proliferate on their platform. And the answer to that is... well, not really. There's already a law for that.

As described in Title 18, Section 2258A, content hosts have a duty to report CSAM — I won't quote the whole thing as more-or-less the entire text is relevant, rather than a specific section, but this is the text describing the duty to report:

"In order to reduce the proliferation of online child sexual exploitation and to prevent the online sexual exploitation of children, a provider—

(i)shall, as soon as reasonably possible after obtaining actual knowledge of any facts or circumstances described in paragraph (2)(A), take the actions described in subparagraph (B); and

(ii)may, after obtaining actual knowledge of any facts or circumstances described in paragraph (2)(B), take the actions described in subparagraph (B)."

I'm not going to break down precisely what those paragraphs are referring to because that would make this post way, way longer, but to summarise: as soon as we find out about it, we have to take specific steps including reporting it to the relevant agencies. We are also granted certain exemptions from the usual restrictions on user data to report identifying information we may have on the offender(s).

To whit, we are already legally compelled to do essentially everything in our power about CSAM (as defined by US law) that we learn about. Blowing up Section 230 isn't going to improve this situation, it's just going to obliterate social media and the internet as we know it. The answer is (must be) technological, rather than legal.

As is something of a theme in my posting, content moderation remains the great unsolved problem of the digital landscape, and any seemingly-easy solution, isn't.

#content moderation#ao3#sufficient velocity#tumblr#facebook#twitter#section 230#my apologies to any actual lawyers who spot errors here#please reblog with corrections if you have them#if you're wondering why it's US law specifically that's so important#that's hegemony for you#there's european union law too but that's way more complicated and I am definitely not qualified to discuss it#you'd need to ask my boss#who will probably not answer that was not a serious suggestion

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The social networking platform Reddit relies on volunteer moderators to prevent the site from being overrun by problematic content—including hate speech—and ensure that it remains appealing for users. Though uncompensated, this labor is highly valuable to the company: According to a pair of new studies led by Northwestern University computer scientists, it’s worth at minimum $3.4 million per year, which is equivalent to 2.8% of Reddit’s 2019 revenue.

[...]

They found that collectively, the whole Reddit moderator population spends 466 hours per day performing moderating actions on the platform at a minimum. This is a lower bound estimate because the study could not account for every single action that might reasonably be construed as moderating. Using the median hourly U.S. rate for similar paid services gleaned from the freelancing platform UpWork ($20/hour), they calculated the $3.4 million per year figure.

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the pose promts, B2 bowser and luigi? I feel like that is just screaming their name sksjdjsksjdjdj

THIS POSE IS SLIGHTLY IMPOSSIBLE BECAUSE BOWSER,,,,,,,BIG,,,,,,

#sorry followers who followed me for like moderately normal content wasdfghjhgf#bowuigi#my art#fanart#answered#doodles

50 notes

·

View notes